Statement #1: “Machines were devised not to do a man out of a job, but to take the heavy labor from man’s back and place it on the broad back of the machine.”

Statement #2: “Less people will have to work in the traditional sense and people will be less willing to do jobs they don’t like. People won’t have to work to survive, and we will have to pay more for less desirable jobs, or automate them, which seems great all around.”

The answer? Nothing.

The first statement is from 1930 and the second is a post on X (formerly Twitter) from 2021. But, otherwise, these statements are describing the same thing: A future in which work is a hobby.

Notably, the first statement is from Henry Ford and the second is from Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI and creator of ChatGPT. But for all the bold proclamations and predictions of industry leaders about the nature of work, the result remains the same.

We’ve been talking about the future forever, and yet it never seems to get here.

If It Ain’t Broke, Don’t Fix It

Henry Ford frequently described a future in which people were mostly free to pursue recreation, education or other nonwork pursuits because most work would be the responsibility of machines. In fact, he’s largely responsible for — or credited with — moving from the six-day work week to the five-day/40-hour work week. That was a significant advancement towards the future of work.

However, in nearly a century, what’s changed? The common definition of full-time work is generally five days a week, approaching 40 hours and most of us would still describe our jobs as grinds. And so here we are. Inertia is a powerful force.

Procrastination Is the Enemy of Innovation

Like a college student who believes they do their best work at the deadline, we’ve waited until change is at our doorstep to start innovating on how work should evolve. Generative AI technologies have sparked organizations to rethink everything from how many employees they have to where jobs should even be done. (Entirely in the office? How quaint.) This might feel like innovation because we’re finally putting action to decades of words, but we’re just doing the bare minimum to get a passing grade.

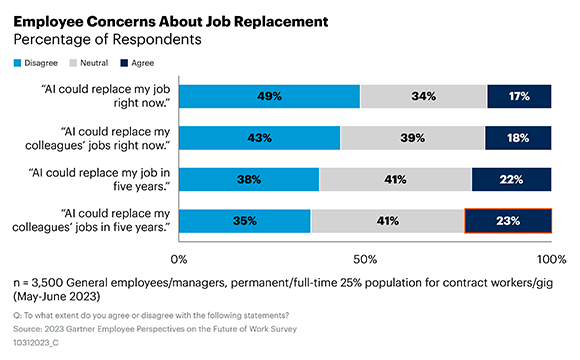

We’re still viewing this debate as a question of false constraints. We leave largely untouched (or marginally changed) questions of what work people need to do, how it gets done (team structures, processes, deliverables, etc.) and the employee value proposition. The lever we think we must, and do, use is number of employees doing the work. Recent data shows that the No. 3 concern for leaders is employee anxiety over their jobs, and rightly so. The figure below shows that concern is justified. Almost 1/5th of employees say generative AI could replace their job today.

For Supply Chain Leaders, the Future is the Past

GenAI and its potential jobs impact is very much of the moment, and much is left to be decided (as illustrated below, leadership is playing coy about the concern their employees feel). But supply chain leaders have seen this before and can bring significant insight and experience to these conversations if they’re willing to step up to the table.

CSCOs on tech-driven mass layoffs. Realistic or not, the conversation around autonomous vehicles and trucking raises questions around layoffs and the future of truck driving. This is analogous to the conversations around what GenAI means for office-based workers who largely write emails and reports. Will we all be laid off? No. Will we talk about it endlessly and ramp up our own anxiety? Yes. Supply chain leaders have already dealt with this anxiety in their own teams — from communications strategies to reassure to workforce development programs to fill skill gaps.

CSCOs on Radical Operations Shifts. Being a supply chain leader means being a manager of constant change. Whether it’s having to dramatically rethink your geographic footprint, your shipping strategy or your in-home delivery policy during the pandemic, rethinking the nature of how work gets done and what needs to get done is an oft-used muscle. GenAI means rethinking basic business operations — how we write emails, how we evaluate supplier bids, etc. — but also big-picture issues like what the future of the workplace will look like with office robo-colleagues.

CSCOs on Defining Employment. Think about the recent threat of a U.S. rail strike and the conversation it sparked about the employee value proposition and benefits. Think about all the conversations, legislation and lawsuits that have occurred over changes to last-mile delivery models, from gig work and questions of compensation and employment status to drones and questions of access to airspace.

With all these employment shifts that supply chain leaders have navigated, it’s not that there haven’t been mistakes, missteps or lessons learned. It’s that organizations risk repeating them if those leaders don’t step up, share their experience and establish themselves as thought leaders within their own organizations. GenAI is forcing an evolution of the future of work. But supply chain leaders have been living in that future for a while.

Article courtesy: Gartner